CONTENTS

Introduction

Part I: Geomantic Symbolism

⠀⠀⠀1.1⠀The Sixteen Figures

⠀⠀⠀1.2⠀Elemental Composition

⠀⠀⠀1.3⠀Qualities of Movement

Part II: Conducting a Reading

⠀⠀⠀2.1⠀Formulating the Question

⠀⠀⠀2.2⠀Casting the Chart

⠀⠀⠀2.3⠀Interpreting the Chart

Part III: Sample Readings

⠀⠀⠀3.1⠀Reading #1

⠀⠀⠀3.2⠀Reading #2

⠀⠀⠀3.3⠀Reading #3

Part IV: Special Techniques

⠀⠀⠀4.1⠀Navigation

⠀⠀⠀4.2⠀Locating Lost Objects

⠀⠀⠀4.3⠀Timing

Further Development

Downloads

⠀⠀⠀Table of Correspondences

⠀⠀⠀Novenary Chart Reference Sheet

⠀⠀⠀Foundations of Nonastrological Geomancy

Notes & References

INTRODUCTION

Geomancy (Greek: geo- + manteia, “earth divination”) is a system of divination estimated to be over a thousand years old, and is widely speculated to have originated in the Arab-speaking regions of North Africa during the Islamic Golden Age. Traders and merchants of that time referred to this practice as`ilm al-raml (“science of the sand”) or khatt al-raml (“cutting the sand”), referencing the desert surface upon which readings were often conducted. Since its recorded emergence, Arabic geomancy has dispersed across multiple cultures to form the diverse divinatory tradition that we know today, inclusive of European astrological geomancy, Malagasy sikidy, and likely West African ifá.1

This guide is intended to introduce the reader to a contemporary variant of geomancy that is designedly free of astrological correspondences, and which uses a nascent six-figure interpretive framework for conducting readings. I began developing this system in 2021, largely inspired by the geomantic tetractys presented in La Géomancie Magique by Robert Ambelain.2 As this system departs significantly from the normative understanding and practice of this art, the contents of this guide should not be considered representative of the broader geomantic tradition.

The sections that follow explain the fundamental symbolic aspects of geomancy and provide detailed instructions for casting and interpreting a chart according to the rules of this variant. Portions of this guide have appeared in previously published material on this blog.

PART I: GEOMANTIC SYMBOLISM

1.1⠀The Sixteen Figures

The practice of geomancy first requires an in-depth understanding of its primary symbols, i.e., the sixteen geomantic figures. These figures can generally be understood as representing common processes, events, dispositions, states, or conditions. Considered apart from their psychological function as aids to self-reflection, the figures can also be regarded as linguistic ideograms that the subconscious can use to communicate nonlocal information to the conscious mind. The anomalous cognitive process by which this occurs is suggestive of a speculative metaphysic, whereby everything in the universe exists as interconnected patterns of information that can be accessed by the subconscious and “uploaded” to conscious awareness—allowing us to perceive people, places, things, or events separated from us by distance, shielding, or time.

The following table illustrates the sixteen figures, their Latin and English names, and their basic conceptual meanings:

| Figure⠀⠀⠀ | Name and Meaning |

|---|---|

| Via (“Way”) – a road or pathway, a journey, change |

| Populus (“People”) – an assembly or gathering, community, society, multiplicity, inertia |

| Conjunctio (“Conjunction”) – interaction, union, connection, crossroads, convergence, exchange |

| Carcer (“Prison”) – restriction, limitation, isolation, delay, obligation |

| Fortuna Major (“Greater Fortune”) – slowly achieved but lasting success by way of individual effort and persistence through adversity, inner strength |

| Fortuna Minor (“Lesser Fortune”) – quickly achieved but ephemeral success by way of luck or outside assistance, outer strength |

| Acquisitio (“Gain”) – increase, profit, obtainment, accomplishment |

| Amissio (“Loss”) – decrease, deficit, relinquishment, failure |

| Puella (“Girl”) – love, harmony, happiness, balance, beauty, receptivity |

| Puer (“Boy”) – energy, force, passion, seeking, eagerness, conflict, rashness |

| Albus (“White”) – peace, wisdom, intelligence, experience, purity, introspection, prudence, detachment |

| Rubeus (“Red”) – violence, carnality, excess, vice, danger, anger, confusion, deception |

| Laetitia (“Joy”) – upward movement, happiness, satisfaction, wellness |

| Tristitia (“Sorrow”) – downward movement, unhappiness, dissatisfaction, difficulty, illness |

| Caput Draconis (“Head of the Dragon”) – beginning, entering, new possibility, opening |

| Cauda Draconis (“Tail of the Dragon”) – ending, exiting, completion, closing |

These conceptual meanings constitute only a fraction of the figures’ full range of possible significations. Over time, you may come to discover other meanings or build associations that speak to your unique relation with and understanding of the figures. Furthermore, the interpretation of a chart will often require an analysis of these meanings along with the figures’ elemental attributes and qualities of movement introduced in the next two sections.

1.2⠀Elemental Composition

In addition to their basic conceptual meanings, each figure is also traditionally considered to be represented or “ruled” by one of the four classical elements, which carry (but are not limited to) the following metaphorical associations:

| Fire | Will, energy, transformation |

| Air | Thought, transmission, movement |

| Water | Emotion, purification, adaptability |

| Earth | Physicality, structure, stability |

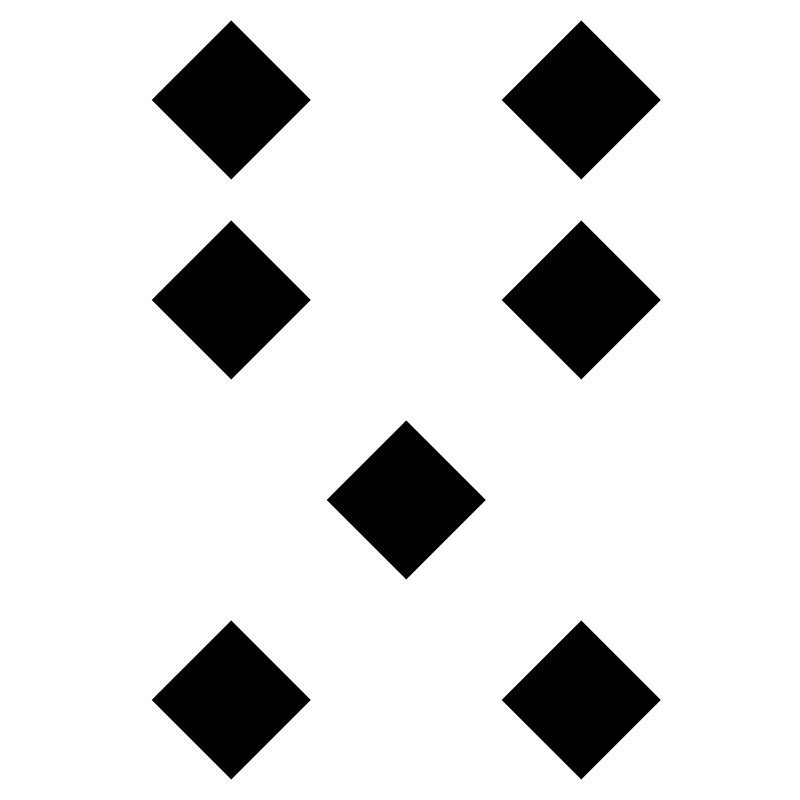

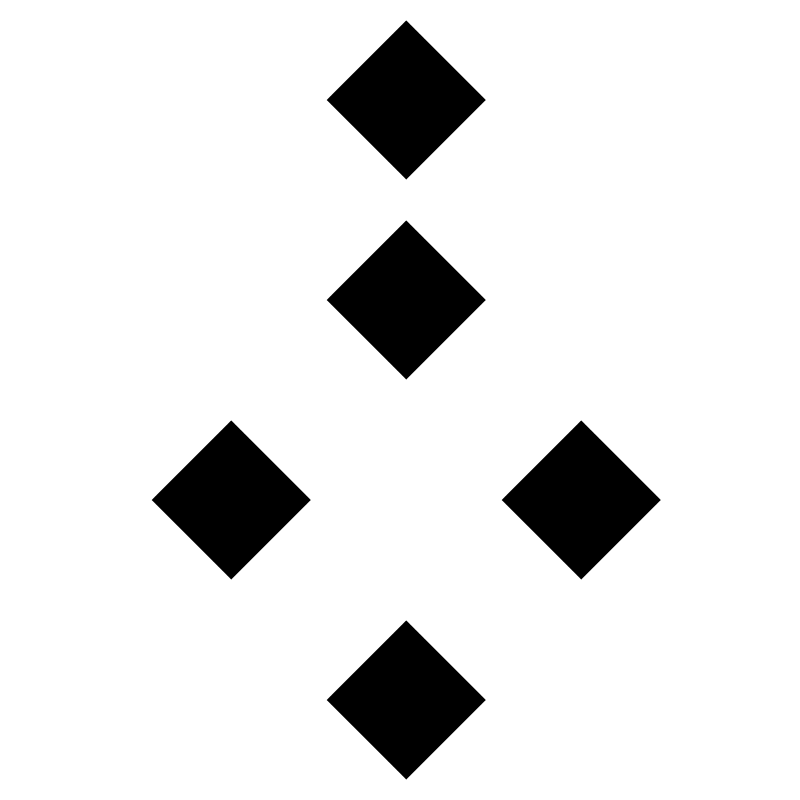

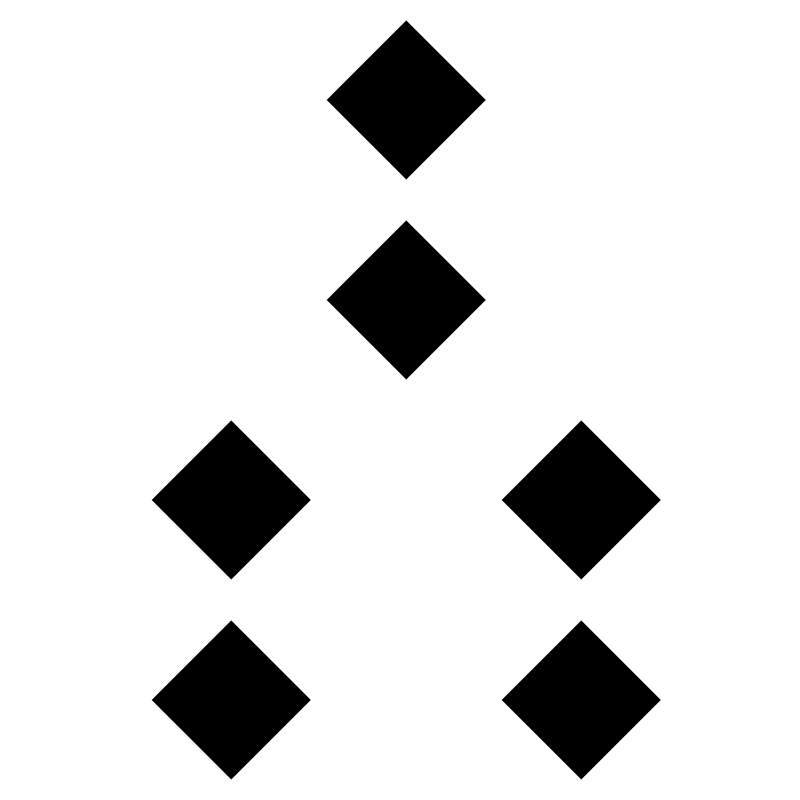

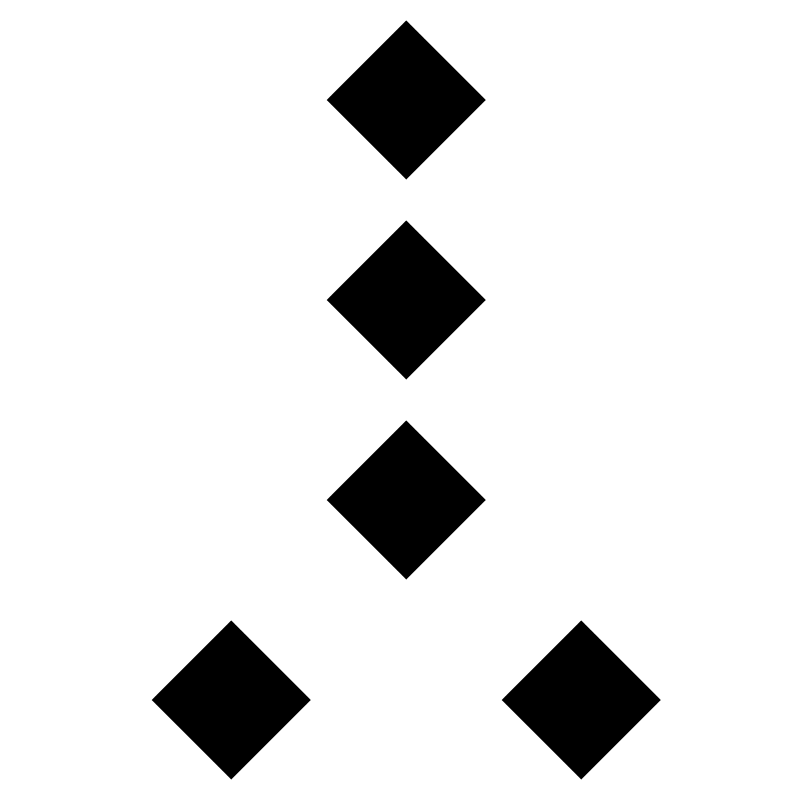

A figure’s ruling element abstractly describes its fundamental nature or temperament, and will often characterize the person, place, or thing that it represents in a reading. In this system of geomancy, the number and arrangement of points in the upper half of a figure determines its ruling element (see table below). The staff (:) symbolizes the element of fire, the downward-pointing triangle (∵) symbolizes air, the upward-pointing triangle (∴) symbolizes water, and the square (::) symbolizes earth.

| Fire |  ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ |

| Air |  ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ |

| Water |  ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ |

| Earth |  ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ |

The sub-element in the lower half of a figure distinguishes it from those sharing the same elemental ruler. It can therefore be understood as a secondary characteristic that further defines or specifies the primary disposition of the figure. For example, within the figure Via, fire is positioned below fire, which is suggestive of the all-consuming nature of transformation. Within Fortuna Major, fire is positioned below earth, evocative of the adversity and change that often precedes lasting success or inner strength. Within Puer, air is positioned below fire, descriptive of the “fueling” dynamic between tenacity and youthful idealism. Within Cauda Draconis, water is positioned below fire, indicative of “extinguishment” as related to endings and finality. Further contemplation of the remaining figures’ ruling elements and sub-elements may reveal similar insights regarding their essential nature.

The binary elemental composition of the figures herein described is based on similar elemental frameworks found in French geomantic literature dating back to the mid-20th century, most notably in the works of Robert Ambelain, but also in later works authored by Alain Le Kern.3 While this system differs significantly from the traditional elemental associations promulgated by Gerard of Cremona and Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, it nonetheless results in congruent correspondences and is conveniently based on the visible structure of the figures.

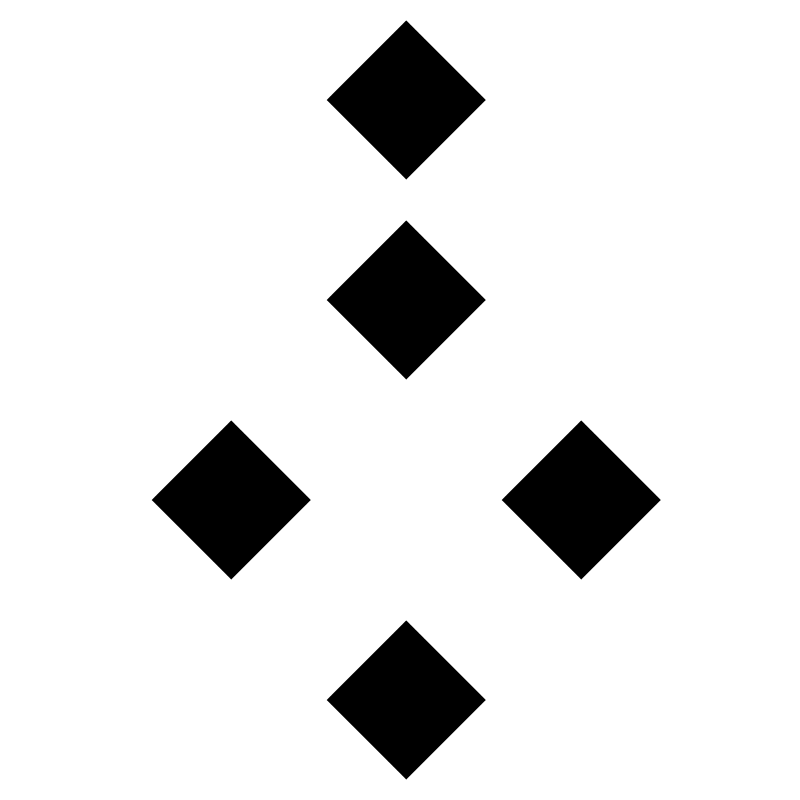

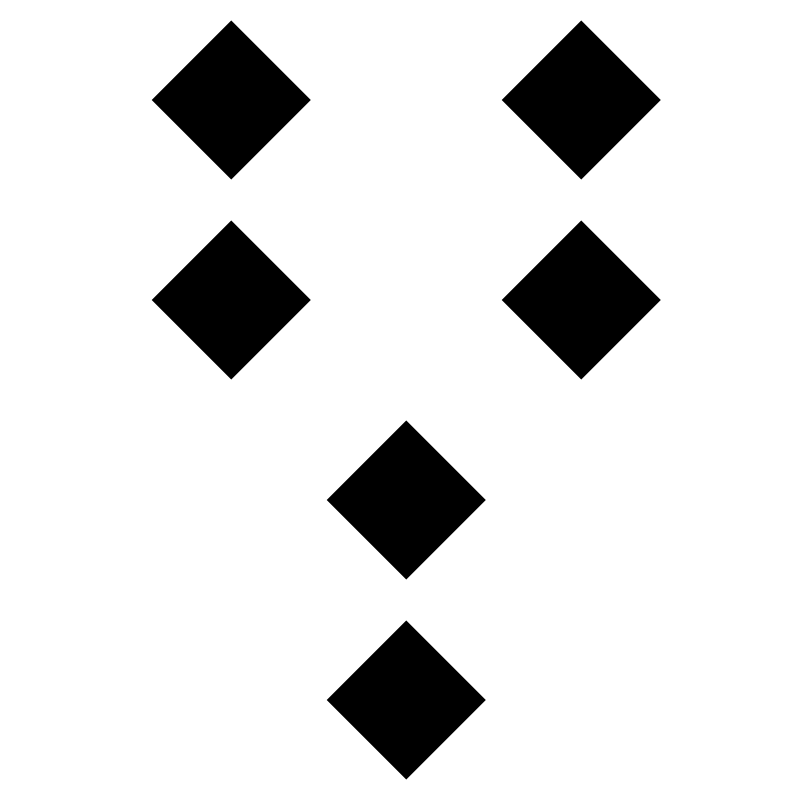

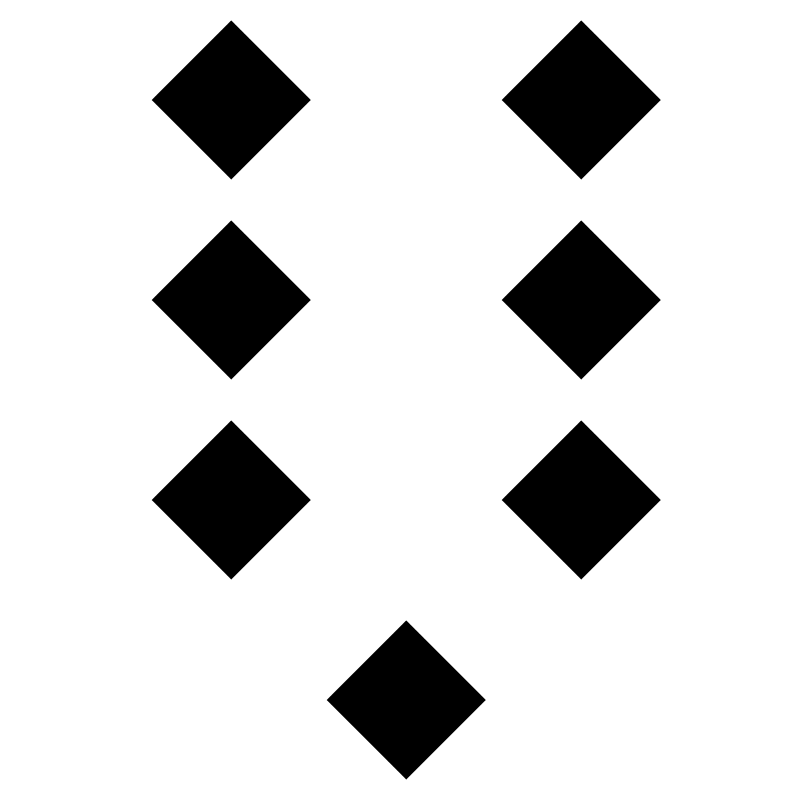

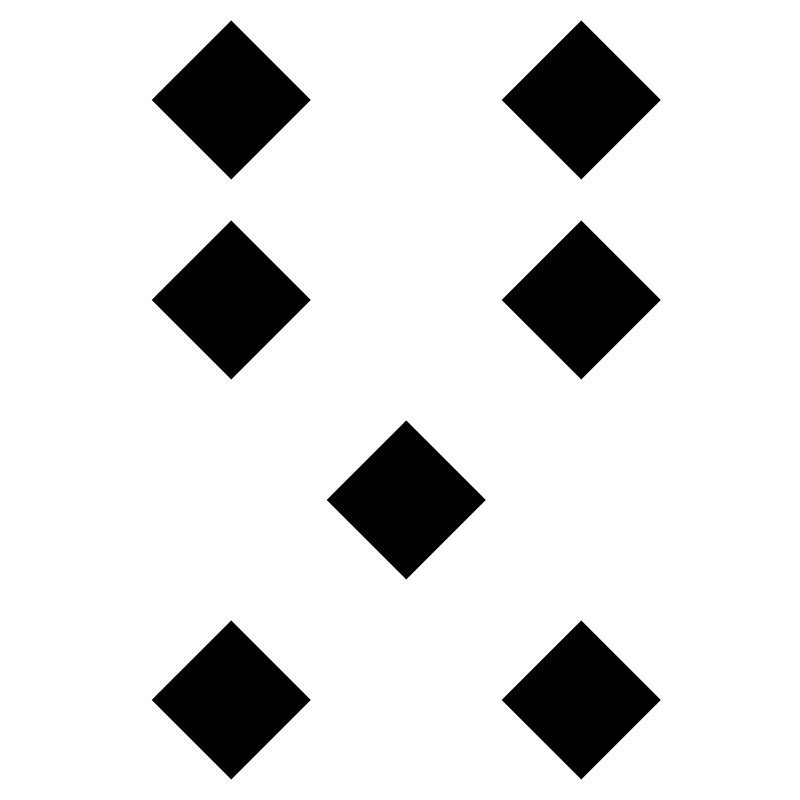

1.3⠀Qualities of Movement

The third layer of meaning inherent to the figures pertains to their qualities of movement, which refers to the directionality of their behavior, influence, or effects. Whereas the ruling element of a figure can describe the general nature of the person, place, or thing it represents in a reading, its quality of movement can sometimes reflect the trajectory of developments occurring in a particular situation. In certain readings, your intuition may compel you to interpret a figure more in terms of its mobility than its conceptual meaning or ruling element, which may be a more accurate description of that figure’s role in the matter being investigated.

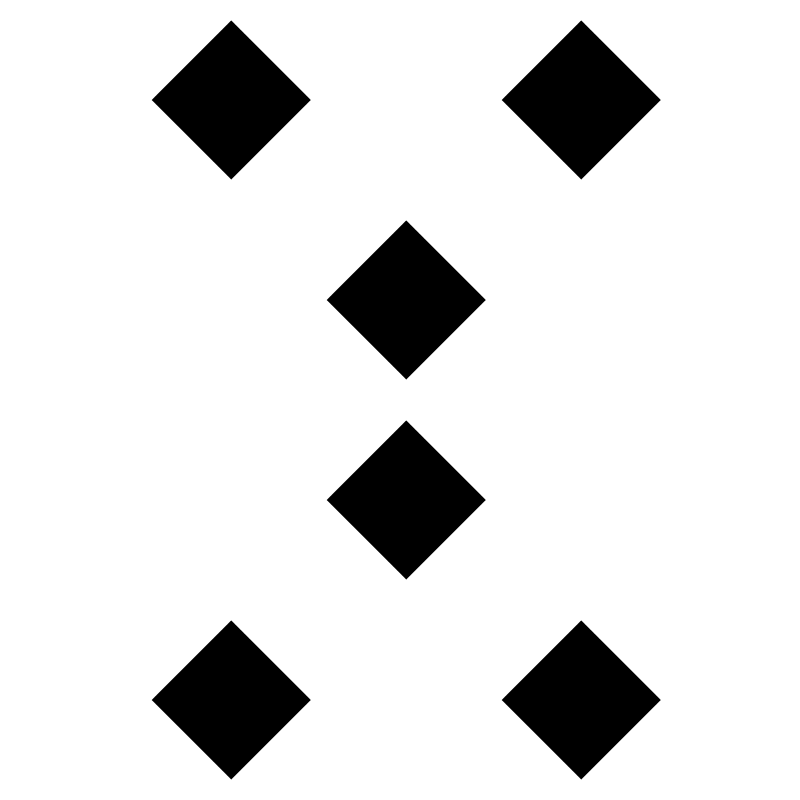

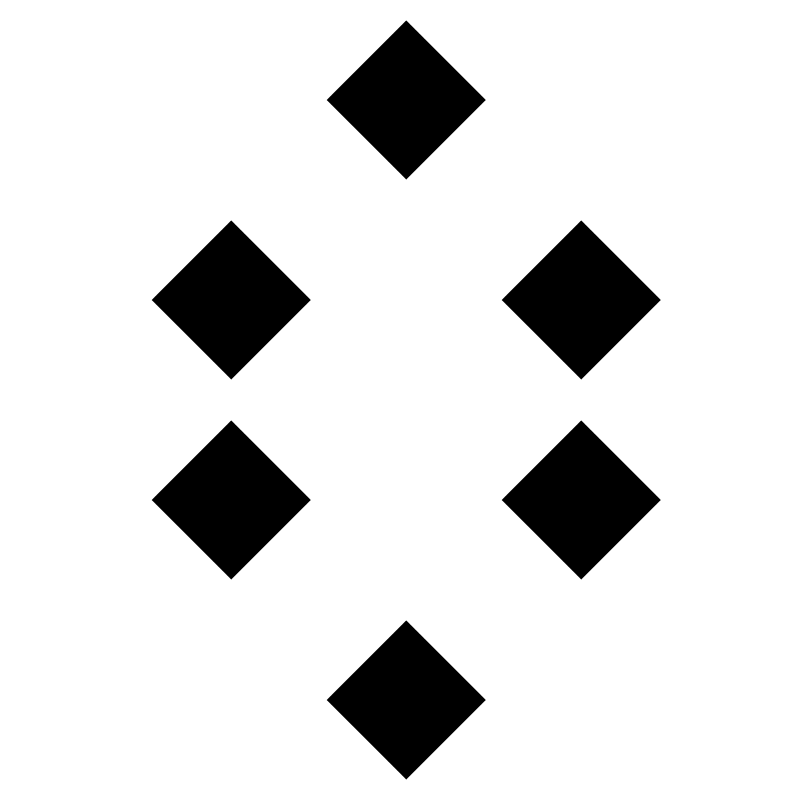

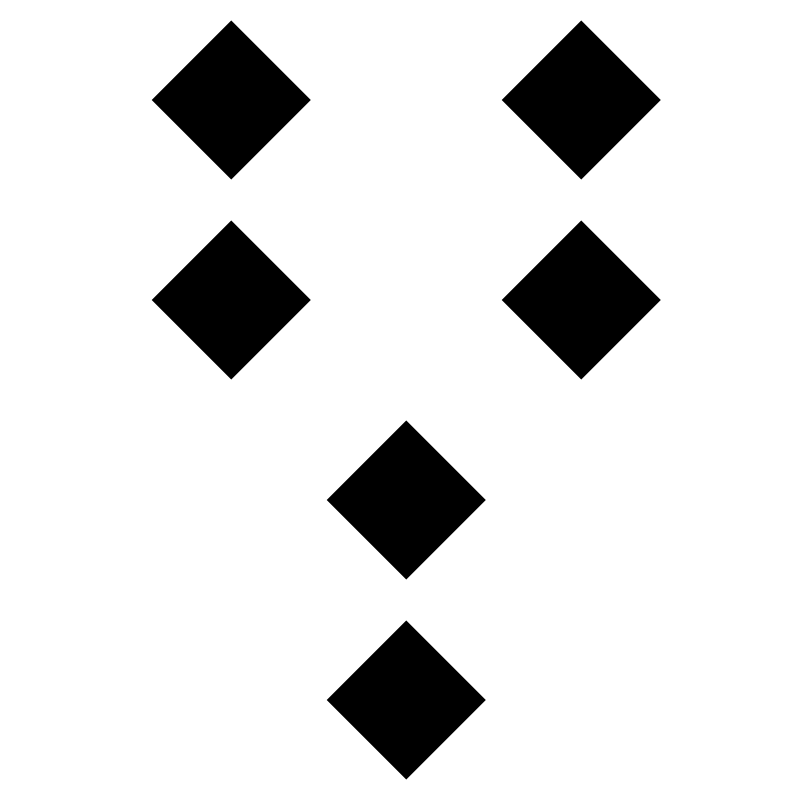

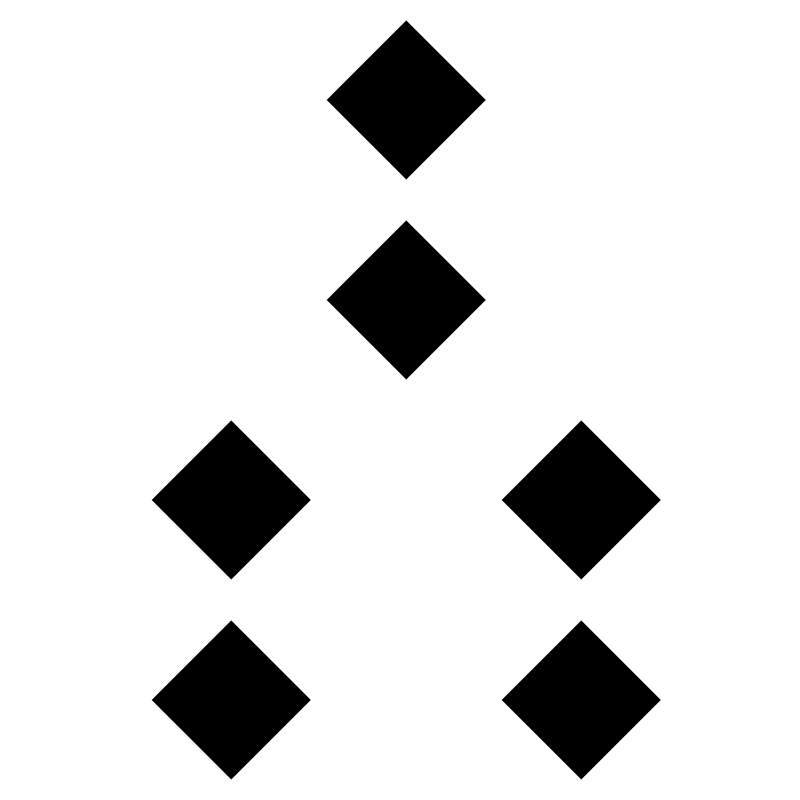

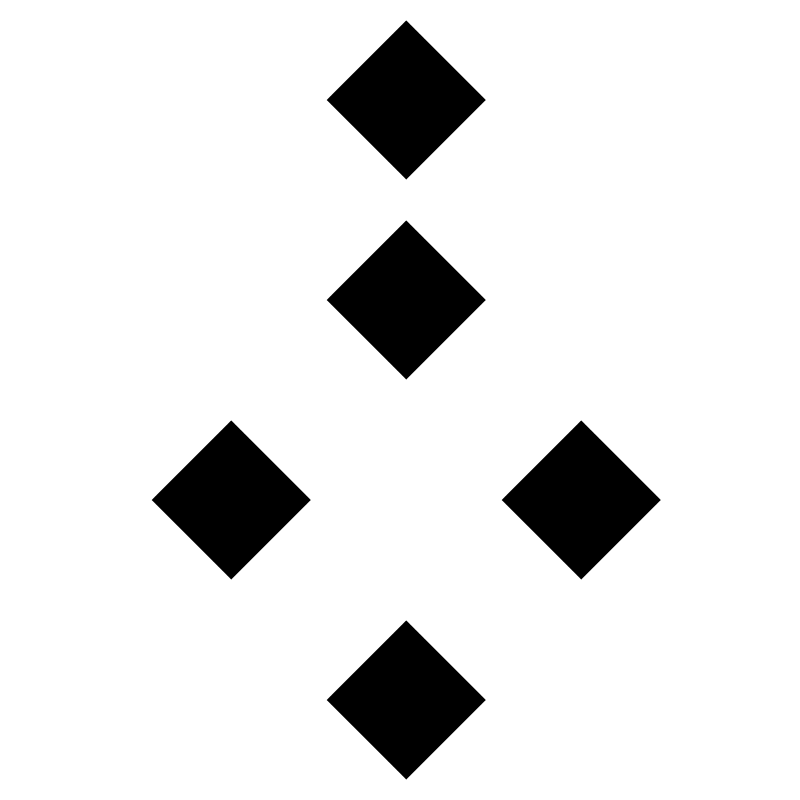

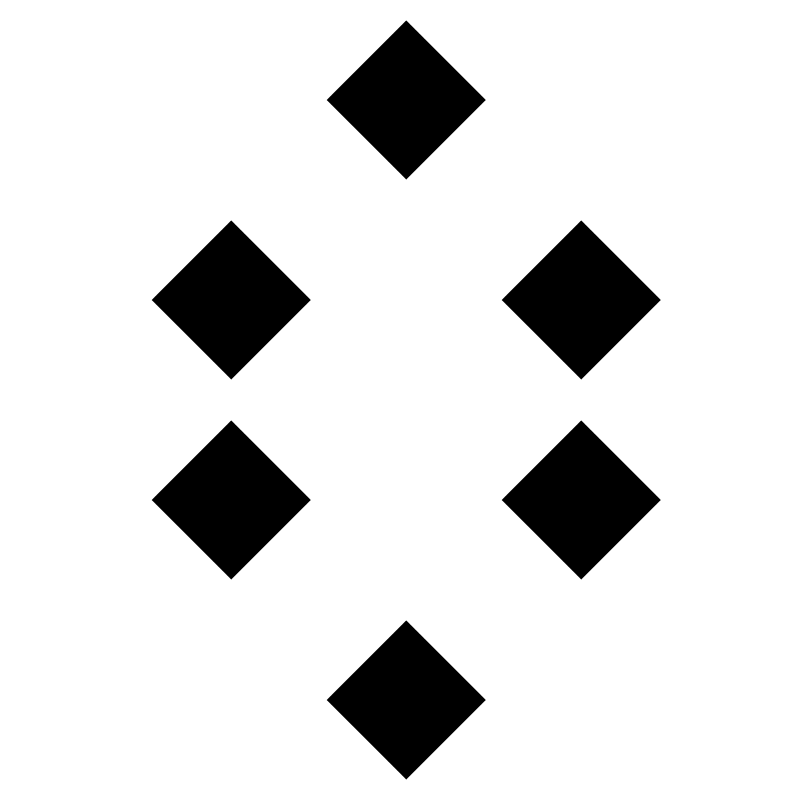

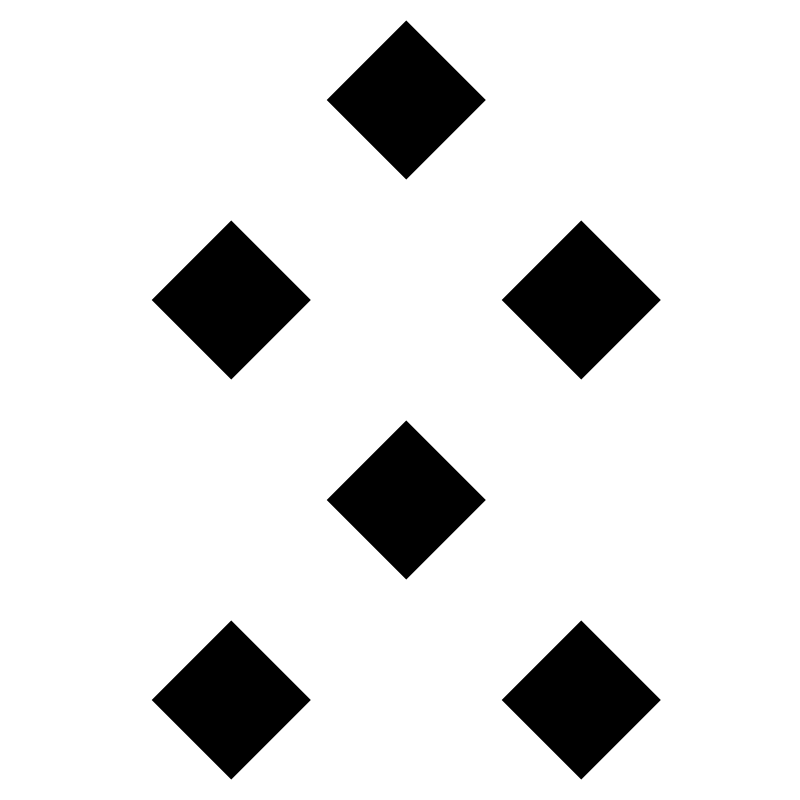

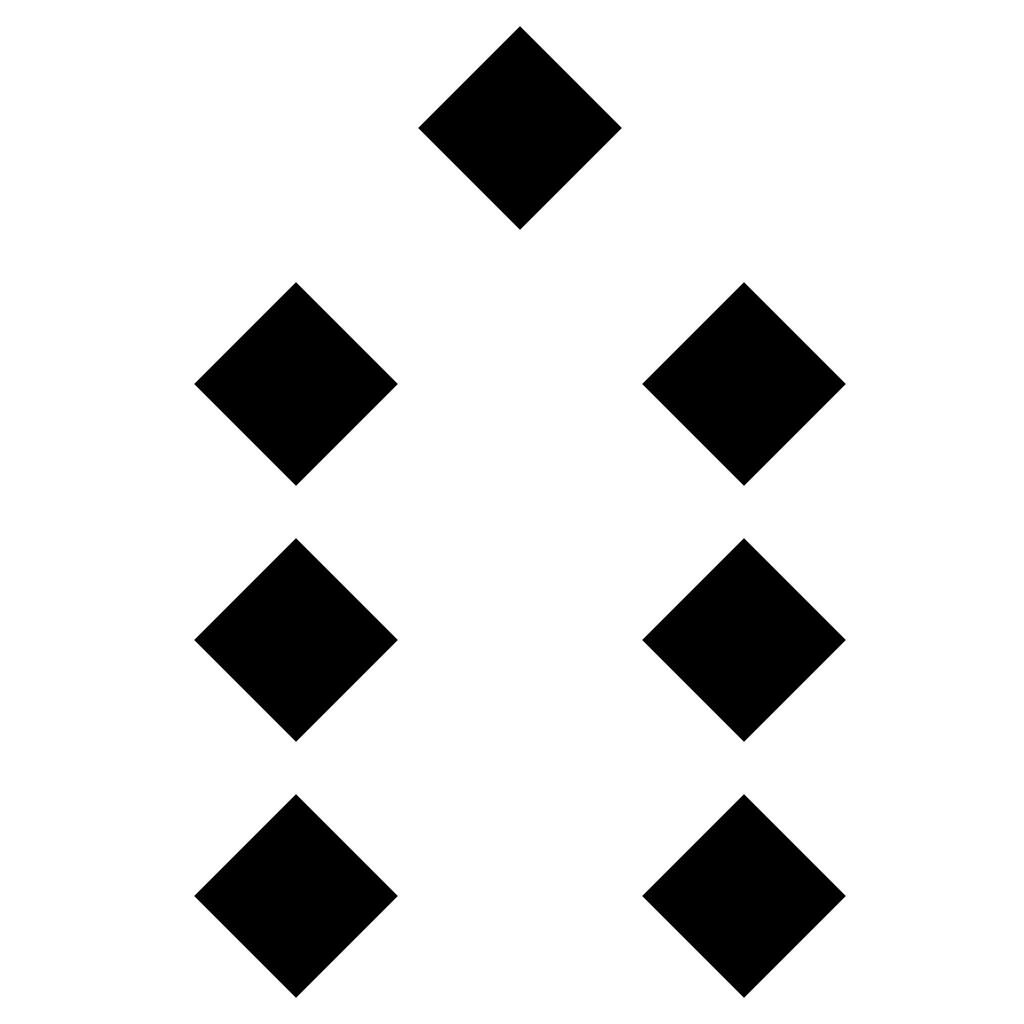

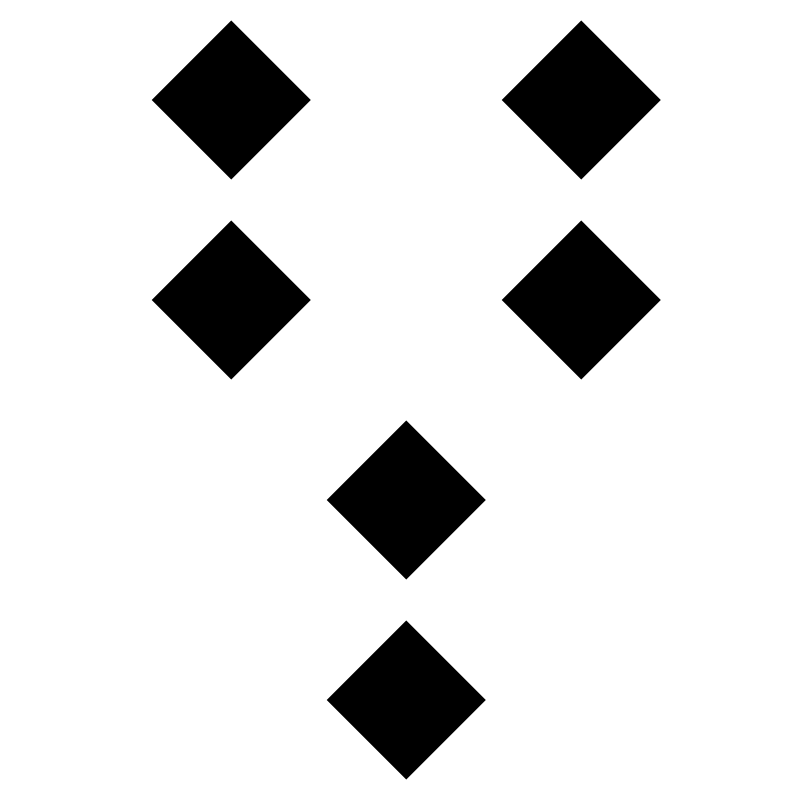

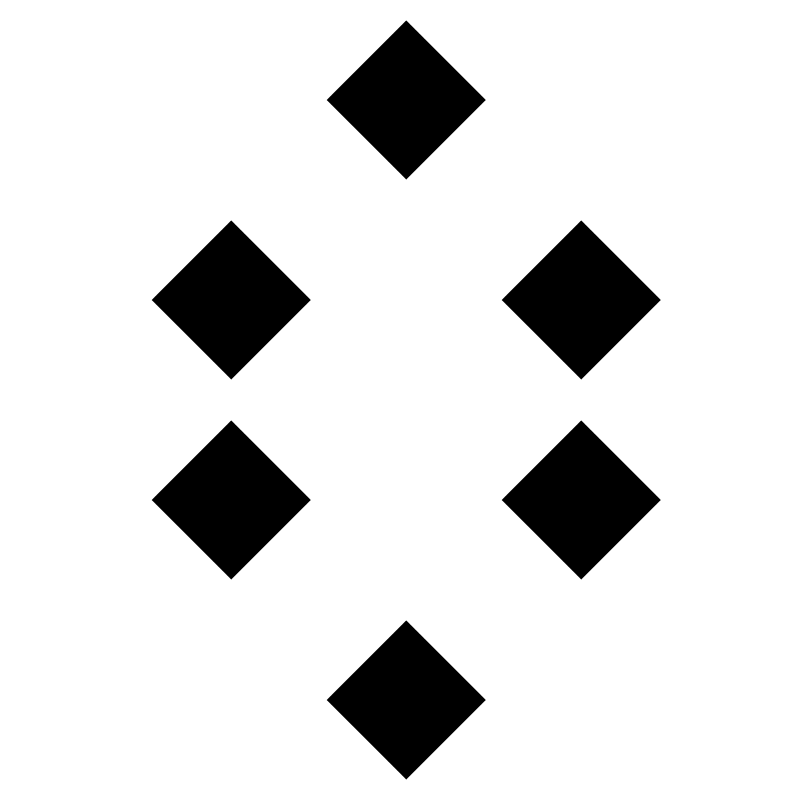

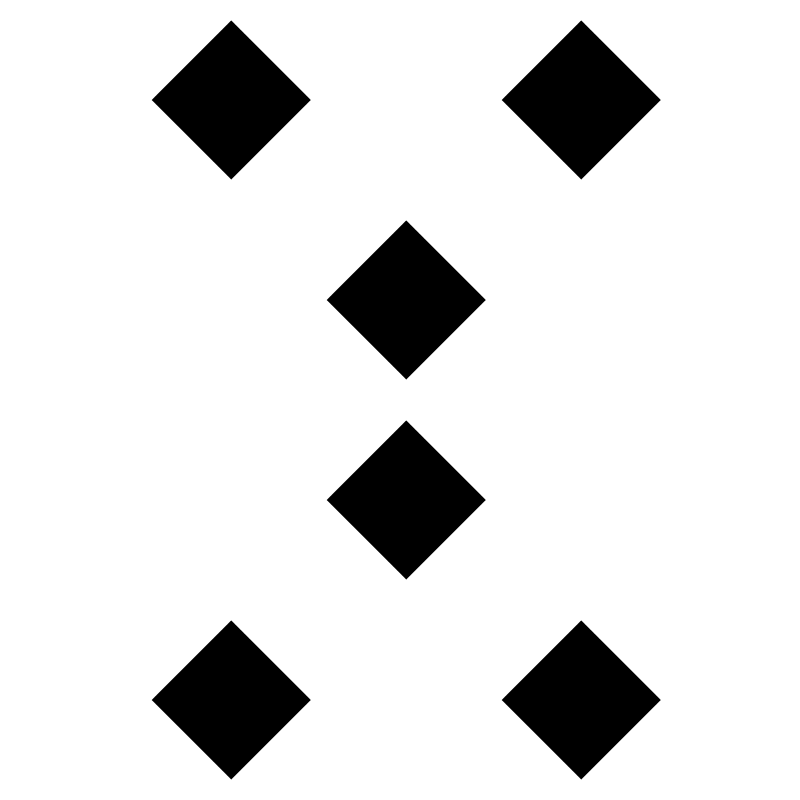

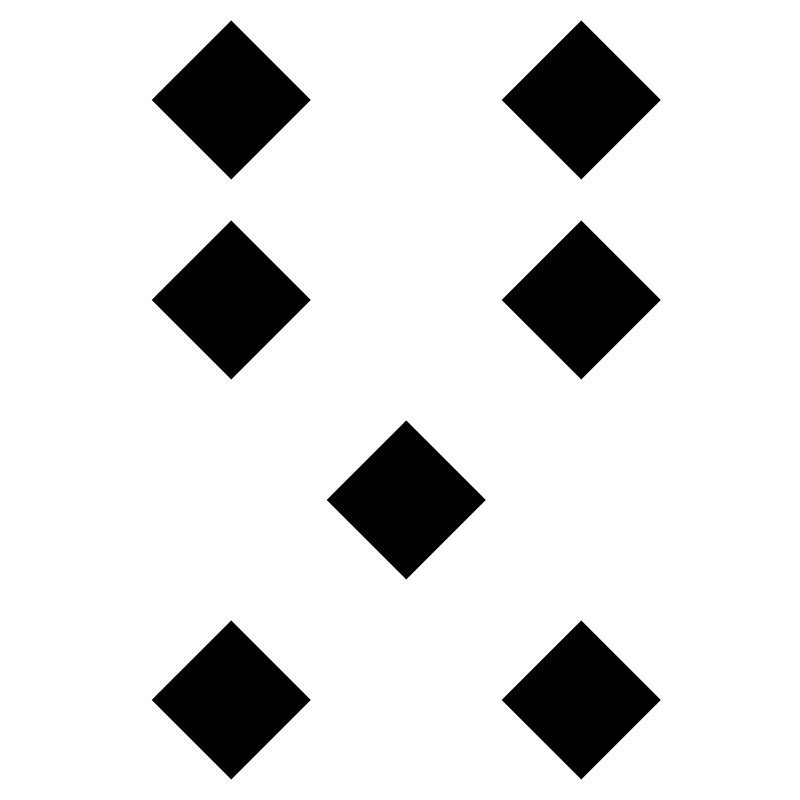

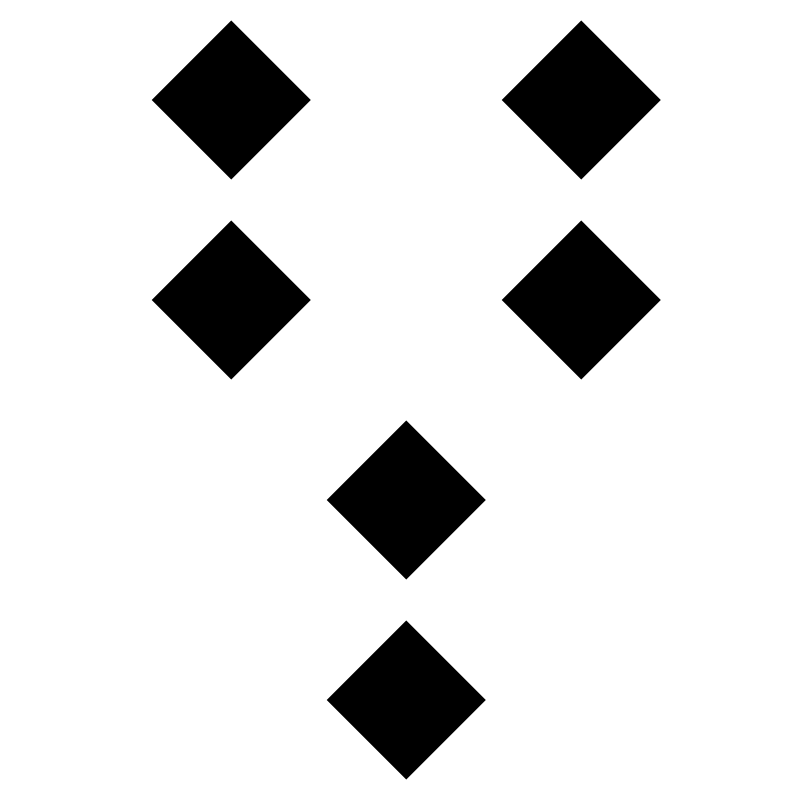

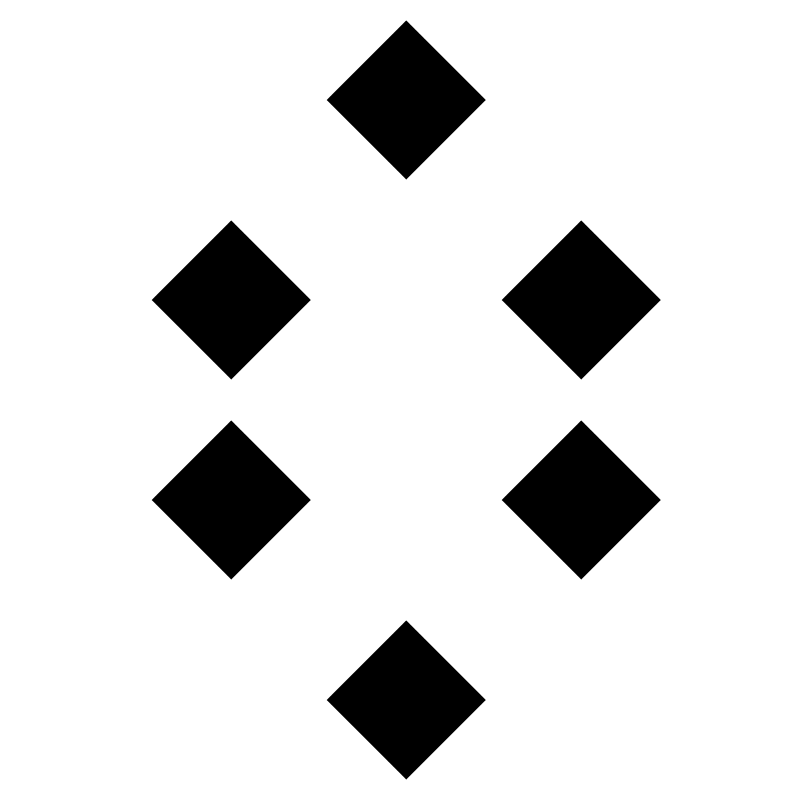

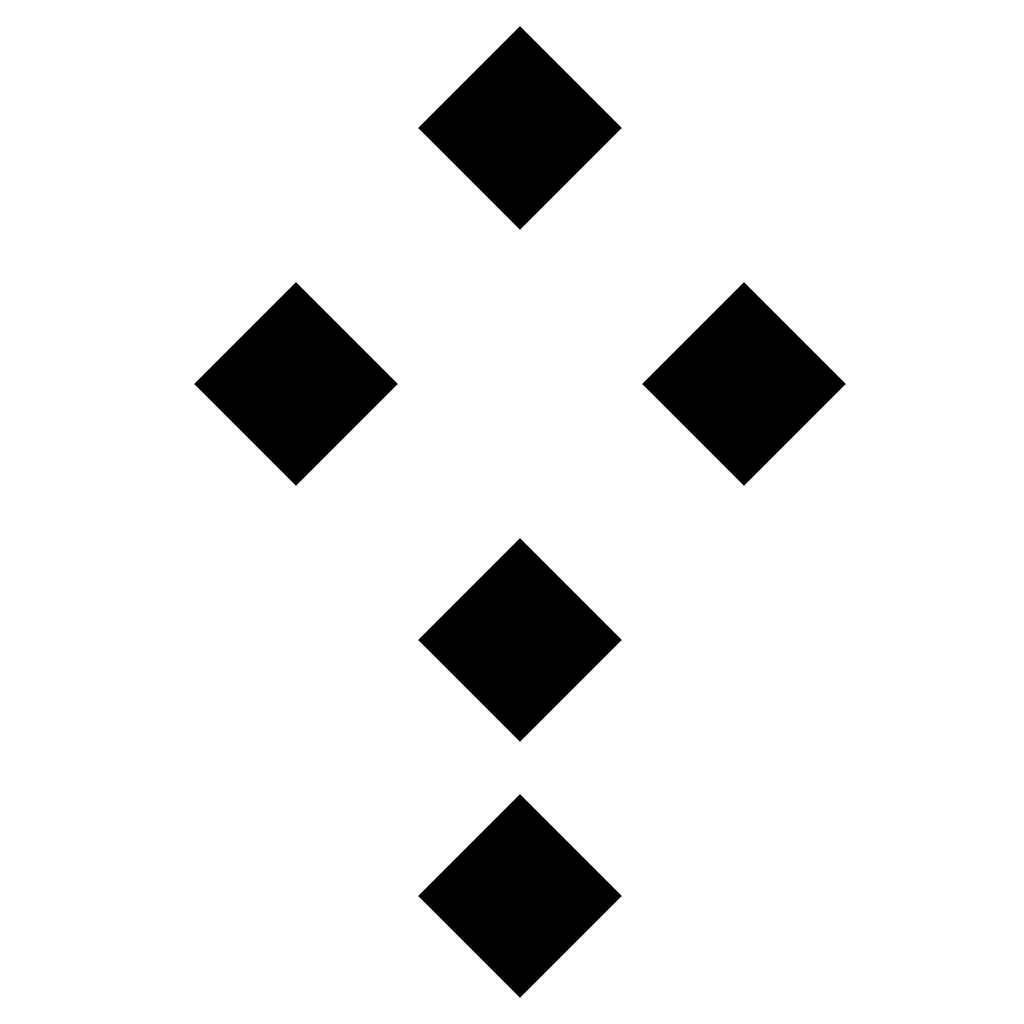

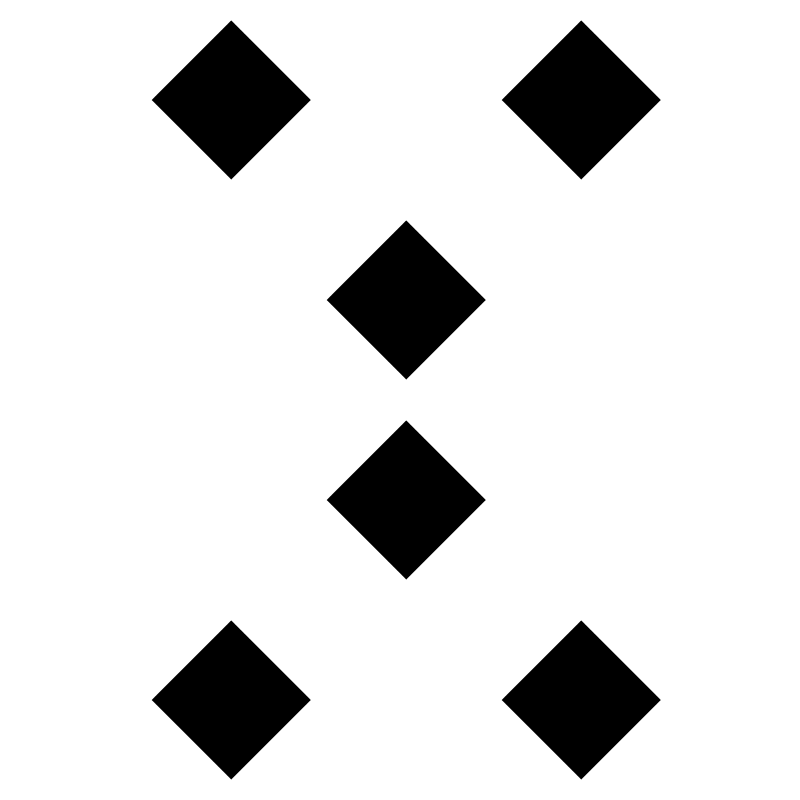

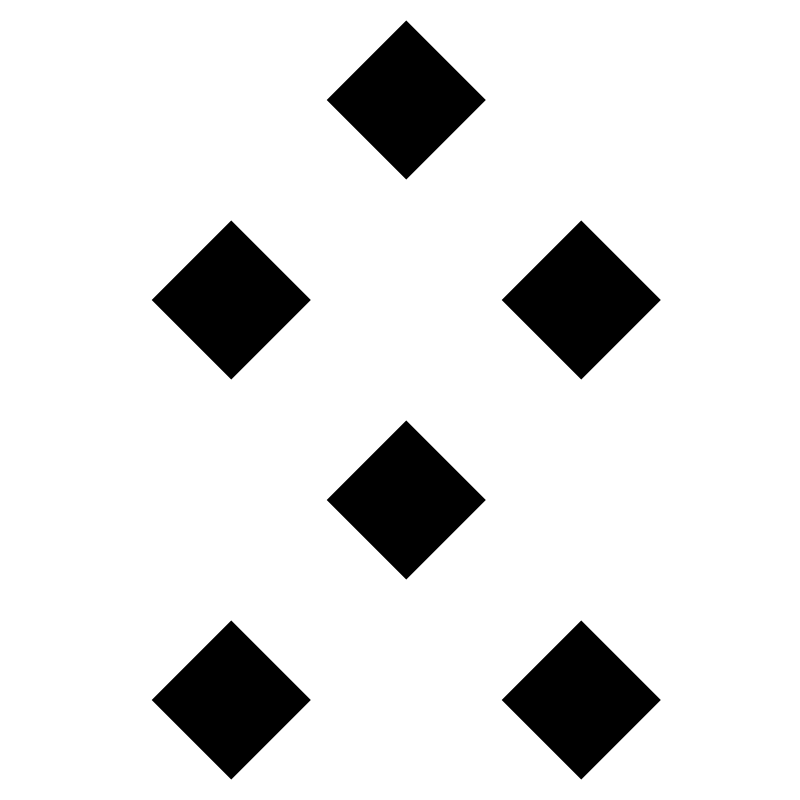

In contrast to the “mobile/stable” division of the figures commonly presented in Western geomantic literature, some forms of Arabic geomancy recognize the following four qualities of movement, which can allow for a more nuanced interpretation of the figures in a chart:

| Entering |  ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ |

| Exiting |  ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ |

| Wavering |  ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ |

| Unmoving |  ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ ⠀⠀ |

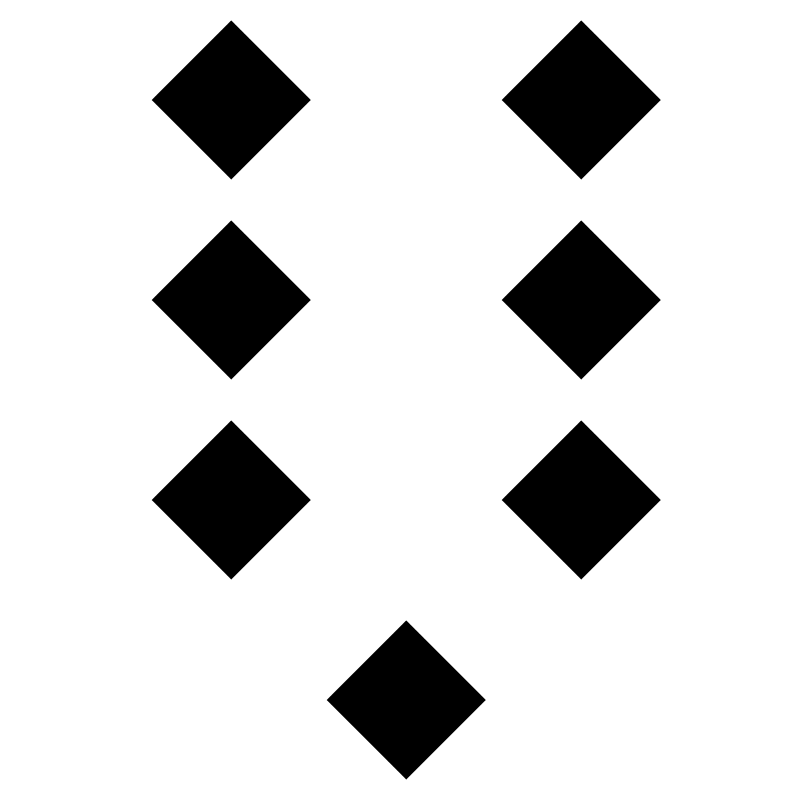

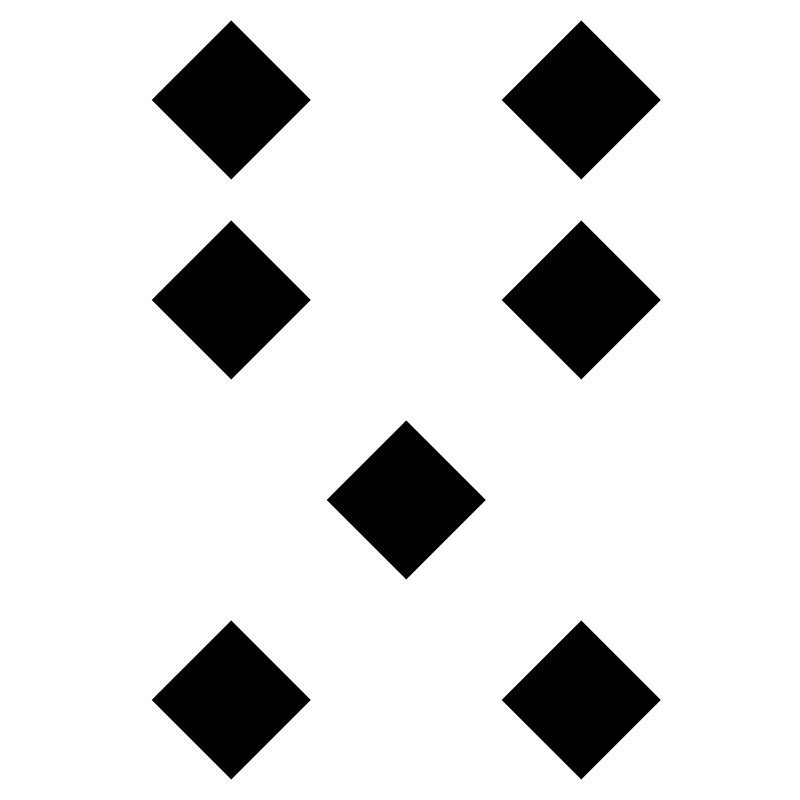

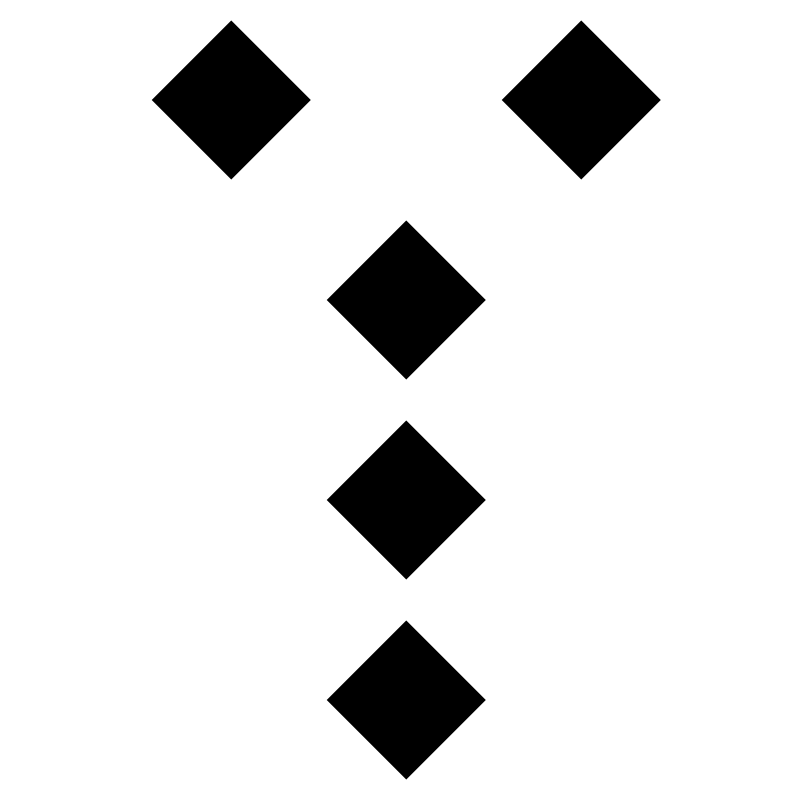

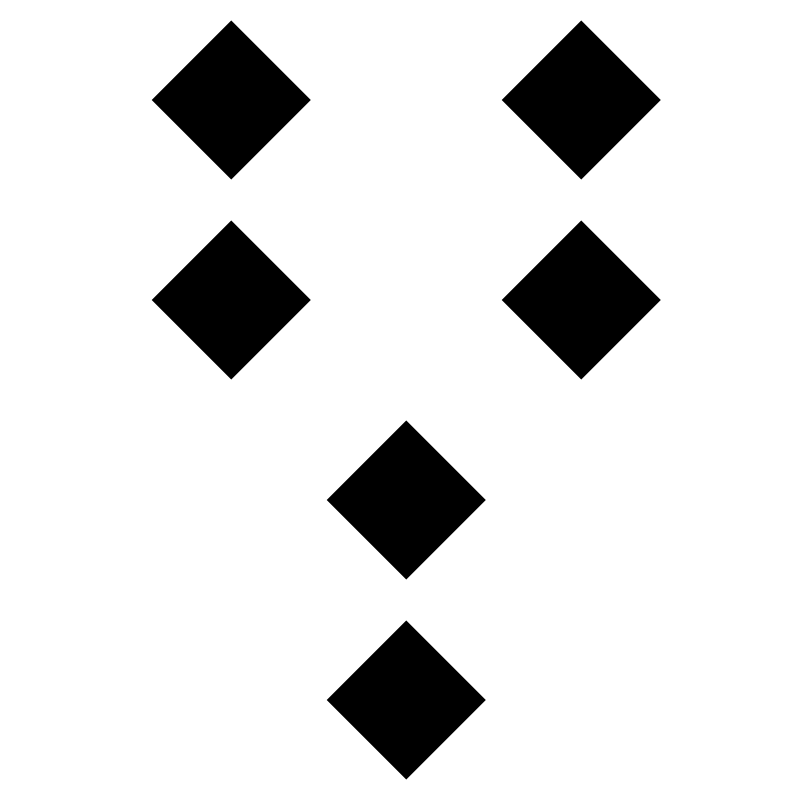

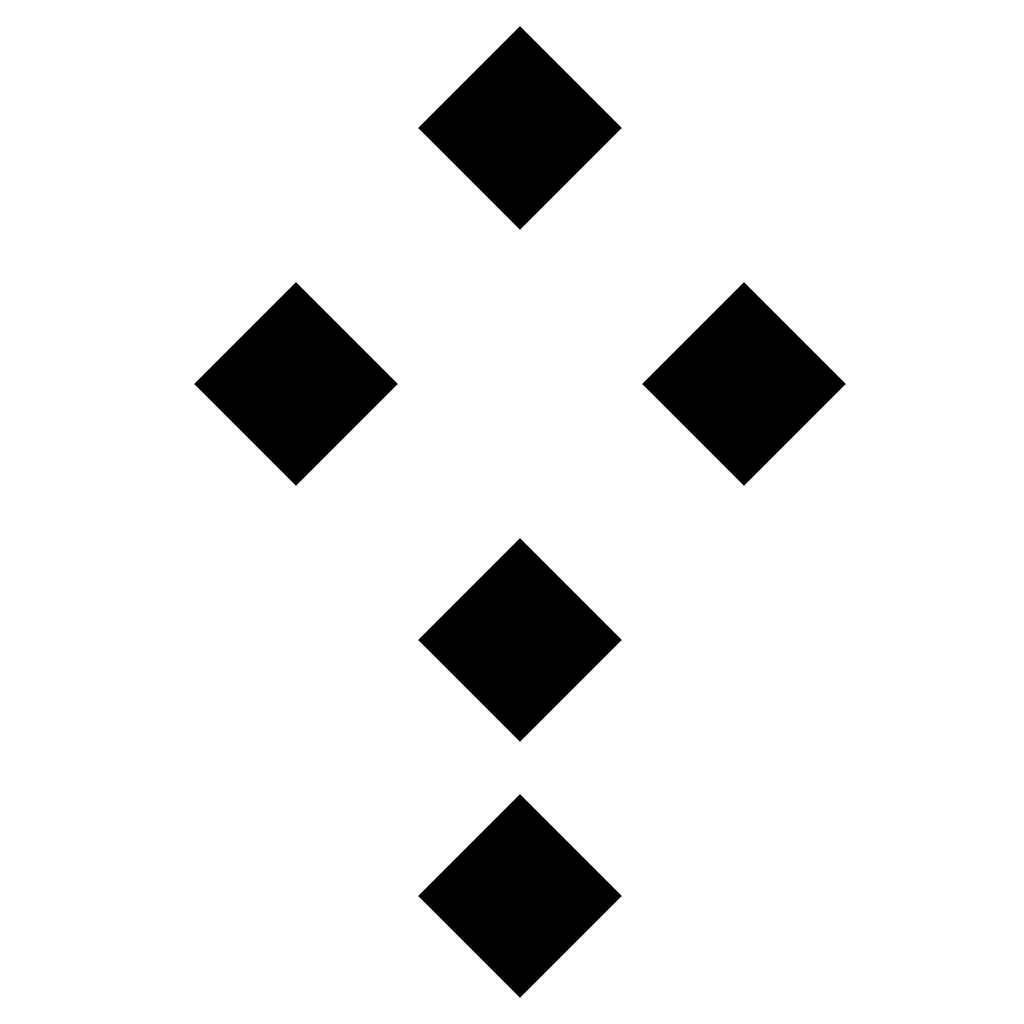

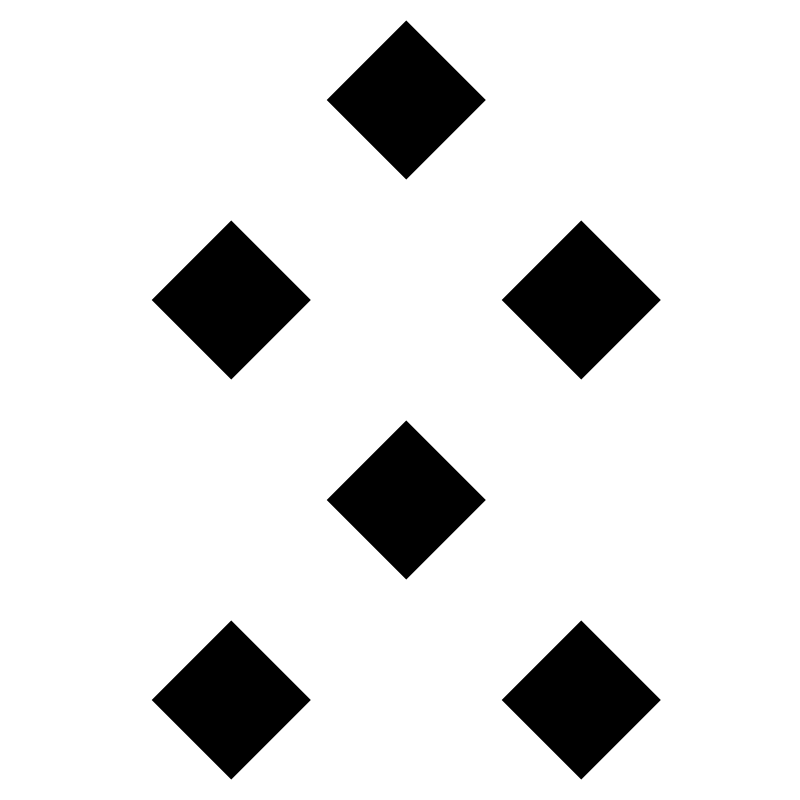

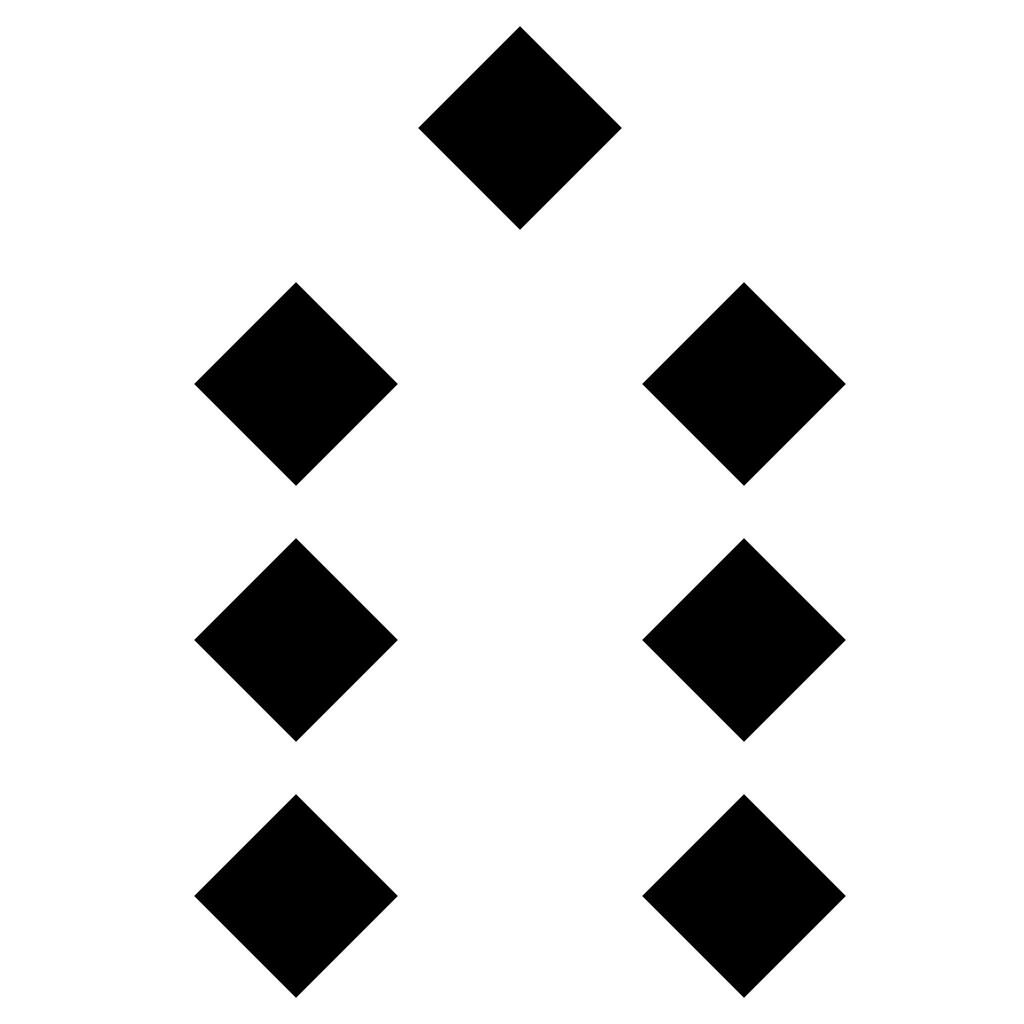

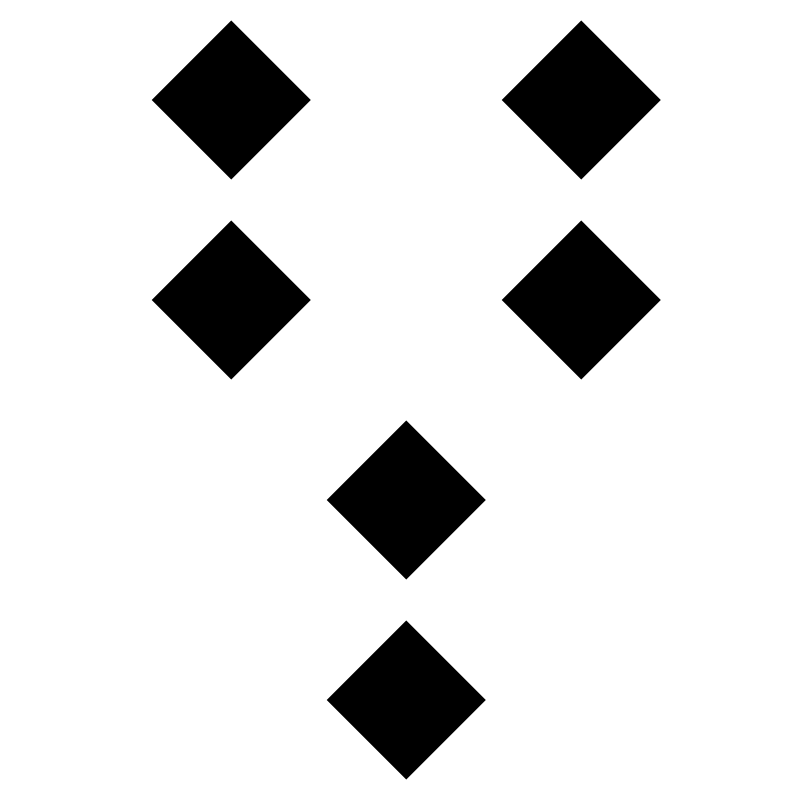

Figures categorized as “entering” possess two points in the top row and one point in the bottom row, which can indicate that the situation, person, or thing they represent in a reading is moving into or toward something.

Figures categorized as “exiting” possess one point in the top row and two points in the bottom row, which can indicate that the situation, person, or thing they represent in a reading is moving out of or away from something.

Figures categorized as “wavering” possess one point in both the top and bottom rows, which can indicate that the situation, person, or thing they represent in a reading is fluctuating or revolving.

Figures categorized as “unmoving” possess two points in both the top and bottom rows, which can indicate that the situation, person, or thing they represent in a reading is unvarying or fixed.

PART II: CONDUCTING A READING

2.1⠀Formulating the Question

Now that you are familiar with the sixteen geomantic figures and their correspondences, it is time to learn how to conduct a reading, which begins with the posing of a question. Due to the complexity and depth of its symbolism, geomancy is capable of answering a wide range of questions, including those concerning one’s relationships, career, and conflicts—as well as questions regarding the spiritual or metaphysical domains of existence.

Whatever the nature of the matter, consideration should be given to the specific formulation of your question in order to get the most out of the reading. Generally speaking, a question can be formulated as either a polar “yes/no” question, or as a nonpolar question framed in terms of “who”, “what”, “when”, “where”, “why”, or “how”. While geomancy is particularly well suited to polar questions, nonpolar queries can be addressed through a closer examination of the figures or the use of special techniques that will be introduced in Part IV of this guide.

Regardless of the interrogative construction you choose, the question should be clear, concise, and direct. Furthermore, a reading should never be conducted for more than one question at a time, as this often results in uninterpretable charts. The following examples attempt to illustrate this point:

| Will X be a good business partner for Y, and will they get along with Z? | ✗ |

| Will X be a good business partner for Y? | ✓ |

| Will X get along with Z? | ✓ |

It can also be helpful to specify the timeframe within which a particular event will potentially occur, as opposed to leaving the temporality of the question open-ended.

| Will I be promoted by the board? | ✗ |

| Will I be promoted by the board this year? | ✓ |

Once you have clearly formulated your question and written it down for later reference, you can then begin the process of casting a chart.

2.2⠀Casting the Chart

A geomantic chart can be understood as a pre-structured interpretive framework, similar to a spread in tarot. While each of the figures carries a specific set of meanings, the positions they occupy on the chart define their role in the matter being investigated. The chart thus serves to guide the reader’s interpretation of the figures and give context to their appearance.

The interpretive framework used in this system of geomancy is referred to as the Novenary Chart and comprises six positions arranged in the form of an inverted equilateral triangle. The positions are numbered from right to left in descending order, reflecting the sequence in which the six occupying figures are generated:

The procedure for populating the chart first requires that you construct three “base” figures from which the remaining three will be derived. Constructing a geomantic figure entails using some randomized means of acquiring four odd and/or even values, such as by rolling a six-sided die four times, each roll corresponding to a row in the figure. If, on the first roll, the number facing up on the die is odd (1, 3, or 5) then the top row of the figure being constructed gets one point; if the number facing up is even (2, 4, or 6), then the top row of the figure gets two points. This process is then repeated three more times to complete the second, third, and bottom rows of the new figure.

For example, if the first roll of the die yields a 2, then the top row of the figure being constructed will get two points. If the second roll yields a 6, the second row of the figure will also get two points. If the third roll yields a 3, the third row of the figure gets one point. Lastly, if the fourth roll yields a 5, the bottom row of the figure will also get one point. In this particular case, the resulting figure would be Fortuna Major, as seen below:

Once you have constructed the three base figures in the manner described above, arrange them horizontally from right to left in the order they were constructed to form the first tier of the chart. For example, if your base figures are Fortuna Major (1st), Conjunctio (2nd), and Fortuna Minor (3rd), they would be arranged in the following manner:

⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀

⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀ ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀

⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀

The process of constructing the base figures is one of the most important phases of the reading, as the subconscious works through the body’s automatistic, physical manipulation of the die to communicate the answer to the question. It is therefore generally recommended that you have some physical contact with the means you choose to construct the base figures, as opposed to using a random number generator or similar “hands-off” methods. Furthermore, it is important that you maintain awareness of the question throughout this process, either by keeping the written query in your line of sight or by repeating it mentally or out loud.

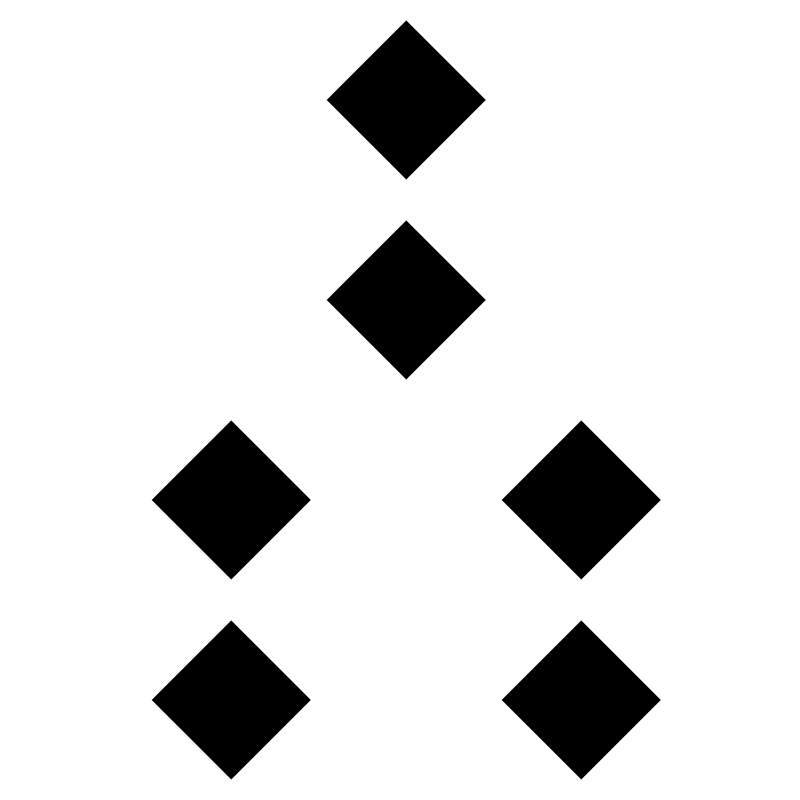

The next step in this procedure entails generating the 4th and 5th figures from the three base figures using an operation commonly referred to as geomantic addition. This is accomplished by firstly adding the number of points in the top row of the 1st figure (Fortuna Major in this example) to the number of points in the top row of the 2nd figure (Conjunctio). Since the sum of that addition is an even number (2 + 2 = 4), the top row of the 4th figure being generated gets two points (if the sum had been an odd number, the top row would recieve one point). This process is then repeated for the second, third, and bottom rows to complete the creation of the 4th figure (Acquisitio), which is positioned below the 1st and 2nd. This same operation is subsequently used to generate the 5th figure (Amissio), which is derived from and positioned below the 2nd and 3rd. Lastly, the 6th and final figure (Via) positioned at the bottom of the chart is derived from the 4th and 5th using the operation just described, thus completing the casting of the chart shown below:

Several important mathematical characteristics of the Novenary Chart are listed below for informational purposes:

- The maximum number of unique charts that can be generated is 4,096, due to the fact that any of the 16 figures can appear in the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd positions (163).

- The highest possible sum of all the points in the chart is 48 (Populus x 6), while the lowest is 32.

- The figure that is produced from the addition of the 1st and 5th will always be the same as the one produced from the addition of the 2nd and 6th, and from that of the 3rd and 4th. These three figures are collectively referred to as the Ternion, which can be checked to verify that no mathematical errors were made during the initial construction of the chart. The potential interpretive value of the Ternion will be discussed later in this guide.

- This interpretive framework is deemed “novenary” on account that a total of nine figures make up the chart when including the three figures comprising the Ternion.

2.3⠀Interpreting the Chart

Now that you know how to cast the chart, it is time to learn what each position means and how to interpret the figures within them. The chart’s positional meanings presented in table below are partially modeled on those within the traditional Shield Chart. However, the familial and judicial nomenclatures associated with the Shield (e.g., Mothers, Daughters, Witnesses, Judge, etc.) have been abandoned in favor of a simple ordinal naming convention:

| Position⠀⠀ | Meaning |

|---|---|

| 1st | The person, place, or thing that is the main focus of the question, i.e., the grammatical subject of the question. |

| 2nd | The heart of the matter, i.e., the central issue or main factor underlying the entire situation. |

| 3rd | The other person, place or thing involved in the matter, i.e., the grammatical object of the question (explicit or implied). If there is more than one object, the querent should assign the most relevant one to this figure before casting the chart. |

| 4th | A factor related to the subject (1st figure) that is either working in favor of or working against the answer to the question (6th figure). If this figure shares the same quality of movement, ruling element, or sub-element with the 6th, then it is accordant with the answer and represents a supporting factor. If this figure does not share any of the said attributes with the 6th, then it is discordant with the answer and represents a hindering factor. The conceptual meaning of this figure will then describe how it is supporting or hindering the answer. |

| 5th | A factor related to the object (3rd figure) that is either working in favor of or working against the answer to the question (6th figure). If this figure shares the same quality of movement, ruling element, or sub-element with the 6th, then it is accordant with the answer and represents a supporting factor. If this figure does not share any of the said attributes with the 6th, then it is discordant with the answer and represents a hindering factor. The conceptual meaning of this figure will then describe how it is supporting or hindering the answer. |

| 6th | The basic answer to the question. |

Whenever possible, the question should be formulated to include at least one grammatical object, which will ensure that the chart is being used in the most effective manner. Generally speaking, and in comparison to the querent-quesited division of the traditional Shield Chart,4 the syntactic structure of the Novenary Chart eliminates much of the confusion that often occurs when the question does not concern neither the querent nor the diviner casting the chart on their behalf.

As previously noted, this system is well suited to polar (yes/no) questions, however, certain nonpolar questions may require the reader to approach the chart somewhat differently. In those cases, the answer to the question will still be revealed by the 6th figure, although additional clarifying details may appear in the 1st, the 3rd, or both the 1st and 3rd, forming a three-part answer. For example, if the question is “Who sent me this gift?”, the 6th might reveal a primary characteristic of the sender, while the 1st may depict a secondary trait or an event associated with the sender that the querent will recognize. The 3rd would then represent something about the gift itself.

Regarding the order in which the figures are to be interpreted, the 6th should generally be examined first, as it is the numerical and symbolic distillation of the preceding figures and represents the general answer to the question. The 1st and 3rd should be analyzed next to understand the subject’s and object’s condition, then the 4th and 5th to ascertain how the subject and object are supporting or hindering the answer. The 2nd should be interpreted last, on account that it reveals the primary causal factor driving the entire matter.

When analyzing the chart, it is important to consider each figure’s conceptual meaning, ruling element, and quality of movement, and to think about how those attributes may be speaking to the question being posed. Peculiar patterns such as mirrored or recurring figures, or a predominance of certain elements and/or qualities of movement in the chart should also be noted, as these occurrences could be conveying something pertinent to the question. Any intuitive impressions that arise should additionally be taken into consideration, as they will often help to orient or guide the interpretation of the chart.

While it is certainly the case that every chart poses a unique challenge to the reader, some charts can be exceptionally difficult to interpret. In these instances, it can be helpful to step away from the reading for a bit and then return to it from a different vantage point, which can sometimes allow previously unnoticed details to become visible. Factors such as one’s physical and/or emotional state can have a significant impact on the ability to accurately interpret a chart, so choosing an optimal time and setting for the reading can also make a big difference. If all else fails, a new chart can always be cast, though there is much that can be learned in the process of working through a complex reading.

Three sample readings are provided in Part III to demonstrate how the chart could be interpreted for several types of questions, while Part IV introduces a number of special techniques that can be applied to certain nonpolar questions.

PART III: SAMPLE READINGS

3.1⠀Reading #1

Is X going to marry Y in the next three years?

The 6th (Fortuna Minor) is an “exiting” figure ruled by the element of fire and conceptually indicates quickly-achieved but ephemeral success, likely suggesting that X will marry Y in the next three years, but also that the union is going to be short-lived.

The 1st (Puer) shows that X is energetic and eager to make the partnership work, though it might also imply that their decision to pursue a marriage with Y is being made in haste. Moreover, the 3rd (Tristitia) may be depicting or foreshadowing Y’s dissatisfaction with the relationship on some level.

The 4th (Laetitia) and 5th (Rubeus) are both accordant with the 6th based on their shared sub-element (earth), which may be an indication that X’s emotional needs and Y’s carnal desires are presently being fulfilled. However, considering that the 6th implies fleeting success, this dual accordance might also suggest that their individual needs will, at some point, come into conflict.

Lastly, the 2nd (Acquisitio) may be conveying that X’s decision to marry Y is primarily being driven by their need to feel a sense of accomplishment.

3.2⠀Reading #2

Will X be out of debt by the end of this year?

The 6th (Tristitia) in this context is an unfavorable “entering” figure ruled by the element of earth, likely suggesting that X will not be out of debt by the end of this year and may even sink deeper before the year is out.

The 1st (Caput Draconis) may be depicting X’s eagerness to start the new year debt-free, though the 3rd (Conjunctio) might imply that a combination of financial factors are contributing to their accumulation of arrears. As Conjunctio possesses a “stationary” quality of movement, it could alternatively suggest that the balance is neither increasing nor decreasing at the present moment.

The 4th (Carcer) is accordant with the 6th based on their shared sub-element (air), possibly suggesting that X’s inability to limit their spending is keeping the balance right where it is. However, the 5th (Laetitia) is an “exiting” figure and is discordant with the 6th, perhaps implying that an upward advancement of some kind (career-related?) may help to lift them out of debt.

Lastly, the 2nd (Cauda Draconis) could be implying that the recent ending or closing of something lays at the heart of X’s struggle to pay down the debt.

3.3⠀Reading #3

What was the main reason X was not selected by the board for the directorial position?

The 6th (Fortuna Minor) perhaps conveys that X was not selected by the board due to the brevity of their success as a supervisor, as opposed to a more consistent track record of accomplishments.

While the 1st (Fortuna Major) may be indicative of X’s subjective sense of achievement, the fire-ruled 3rd (Via) is a “fluctuating” figure that can signify change, likely indicating that the board was on the fence regarding X’s promotion, or went back and forth on their decision between X and another candidate.

The earth-ruled 4th (Tristitia) is discordant with the 6th, possibly suggesting that X’s success as a supervisor was short-lived due to a decline in their department’s performance. However, the 5th (Puer) is accordant with the 6th based on their shared ruling element (fire), which might be an indication that the board considered the determination and energy that X showed as a supervisor.

Lastly, the 2nd (Albus), a “stationary” figure ruled by the element of earth, likely suggests that X’s knowledge and experience were ultimately the deciding factors.

PART IV: SPECIAL TECHNIQUES

4.1⠀Navigation

Readings conducted for navigational questions such as “In which direction is X traveling?” or “From which direction will X arrive?” often require the use of interpretive methods that associate each figure with a precise bearing. The 8-point geomantic compass shown below can be employed for this purpose, as it makes unique use of the figures to represent the cardinal and ordinal directions:

Each direction is represented by two figures, which are paired based on their shared quality of movement, shared ruling element, and the complementary nature of their sub-elements (air feeds fire, water nourishes earth). The pairs are arranged around the compass in consideration of the figures’ conceptual meanings, and in such a manner that aligns their ruling elements with the seasons I have come to associate with the eight directions. As a result, the compass additionally depicts the clockwise cycle of the four seasons as seen below, allowing the figures to also serve as indicators of time in certain readings:

| North | Early to mid-winter |

| Northeast | Mid to late winter |

| East | Early to mid-spring |

| Southeast | Mid to late spring |

| South | Early to mid-summer |

| Southwest | Mid to late summer |

| West | Early to mid-autumn |

| Northwest | Mid to late autumn |

When using this compass, the 6th figure reveals the direction in answer to the question, which should be ascertained in relation to true north. If true north cannot be determined, the direction should be estimated in relation to the position of the reader themselves. The remaining figures in the chart should then be examined for details regarding the subject and/or object of the question.

Since each pair contains one figure with an even number of points and one with an odd number of points, this compass can also be used by practitioners who work with the traditional Shield Chart independently of the astrological House Chart, as the shield only permits a figure with an even number of points to appear as the Judge, owing to its unique mathematical structure.

4.2⠀Locating Lost Objects

The two methods presented in this section can be used to locate something that was lost or has gone missing, a common application of geomancy made possible by its versatile symbolism. These techniques are ideal for readings conducted to answer questions such as “Where are my keys?”, “Where did X leave their wallet?”, etc.

Impressionistic Method

Once the chart has been cast, it should then be examined for clues revealing the precise whereabouts of the object by giving careful consideration to each figure’s full range of meanings and correspondences. The 6th figure will reveal a primary clue, such as the general nature of the location, its main characteristic, the type of activity occurring there, or something relevant to the querent’s/owner’s connection with it. Depending on how the question was formulated, the 1st and 3rd figures will either convey something about the person searching for the object or the condition of the object itself. The 4th and 5th figures, depending on their accordance or discordance with the 6th, will either represent a factor that might contribute to the object’s recovery or something preventing it from being found. The 2nd figure, which usually represents the heart of the matter, will describe the causal factor that initially led to the object’s disappearance. Lastly, intuitive impressions and/or unusual patterns in the chart should also be taken into consideration, as they may be communicating something pertinent to the object’s location.

Representational Method

The table below lists eight possible answers to a question about a lost object. Each answer is represented by one of the figure pairs introduced in the previous section. Once the chart is cast, the 6th figure and its corresponding location/status provides the general answer:

| Not lost but overlooked |

| In the querent’s home |

| In a stationary vehicle or craft |

| In a non-residential building |

| In motion |

| Outdoors |

| In someone else’s home |

| Discarded or destroyed |

The remaining figures in the chart are to be interpreted according to their usual conceptual meanings, ruling elements, and qualities of movement.

4.3⠀Timing

Readings conducted to ascertain the timeframe in which an event is likely to occur can be handled in a number of ways. The simplest and most common approach entails reformulating the “when” question into a “will” question, which can then be answered with a “yes” or “no” depending on the perceived favorability or unfavourability of the 6th figure. For example, rather than asking “When will I graduate?” or “When will I find a job?”, one could ask “Will I graduate next year?” or “Will I find a job within the next three months?”. If necessary, successive charts could be cast to narrow down the timeframe even further, e.g., if we know that event X will not occur before date Y but will occur by date Z, we can then conduct another reading to identify a more precise period or a specific date.

In situations where an estimated timeframe cannot be determined, the correspondences listed in the table below can be used. Similar to the previous methods, this system utilizes eight pairs of figures to represent specific timeframes, potentially reducing the need for successive charts to narrow down the range:

| Already occurred |

| Within an hour |

| Within a day |

| Within a week |

| Within a month |

| Within a year |

| After a year or more |

| Will not occur |

The eight pairs are distributed evenly among eight timeframes and are arranged according to the density of their ruling elements and sub-elements, with the elementally “lighter” pairs (fire and air) given to the first four, and the heavier pairs (water and earth) to the second four.

When using this method, the 6th figure and its corresponding timeframe is taken as the answer. The preceding figures are to be interpreted according to their normal range of meanings.

FURTHER DEVELOPMENT

This guide attempts to put forth a complete system of nonastrological geomancy in both theory and practice. It is my hope that this work will mark the emergence of a distinctly terrestrial school of geomantic divination, one which will eventually evolve beyond the interpretive framework and techniques introduced here. Those adopting this system are therefore encouraged to innovate and experiment with new approaches and techniques capable of exceeding the limitations of the current model.

For example, there are two aspects of the Novenary Chart that are currently without an interpretative function, but which could be creatively employed to expand the chart’s capabilities. The first is the total number of points in the chart, which has historically served a number of purposes in traditional readings.5 The second aspect is the Ternion, which currently only serves to mathematically validate the chart, but which could be assigned a special positional meaning to convey something relevant to the outcome of the situation being investigated, or perhaps some detail concerning the querent or the diviner casting the chart on their behalf.

DOWNLOADS

Table of Correspondences

The table of correspondences below can be used as a quick reference sheet when conducting readings. The 1st column depicts the sixteen geomantic figures. The 2nd column presents the Latin names of the figures. The 3rd column lists each figure’s English name and conceptual meanings. The 4th column depicts each figure’s ruling element and sub-element using Western alchemical symbolism. The 5th column lists each figure’s quality of movement. The 6th column lists each figure’s corresponding compass direction. The 7th column lists each figure’s corresponding season. The 8th column lists each figure’s corresponding time frame. The 9th column lists each figure’s corresponding location.

Novenary Chart Reference Sheet

The following reference sheet contains the Novenary Chart’s positional meanings, as well as the figures’ qualities of movement, ruling elements, and sub-elements.

Foundations of Nonastrological Geomancy

A PDF reproduction of this post is provided below for offline reading.

Notes & References

- ^ A more in-depth historical overview can be found in Terrestrial Astrology: Divination by Geomancy by Stephen Skinner (1980), and in Islamic Geomancy and a Thirteenth-Century Divinatory Device by Emilie Savage-Smith and Marion B. Smith (1980).

- ^ Robert Ambelain, La Géomancie Magique (Paris: Éditions Adyar, 1940), 200–202.

- ^ Robert Ambelain, La géomancie arabe et ses miroirs divinatoires (Paris: Robert Laffont, 1984), 54; Alain Le Kern, La géomancie, un art divinatoire: Premiers élements de géomancie (Paris: Éditions du Rocher, 1978), 39–47; Robert Ambelain, La géomancie magique (Paris: Éditions Adyar, 1940), 21–25.

- ^ Christopher Cattan, The Geomancie of Maister Christopher Cattan, Gentleman, trans. Francis Sparry (London: John Wolfe, 1591), 160–161.

- ^ In a traditional reading, the sum of the Shield Chart is sometimes used to determine whether the outcome announced by the Judge will occur quickly, slowly, or at the exact time specified in the question. The earliest use of the chart sum for this purpose in Western geomancy can be found in the 13th-century works of Pietro d’Abano, most notably within Modo judicandi questiones secundum Petrum de Abano Patavinum (Pietro d’Abano, Munich, Ms. lat. 489, fol. 230, as quoted in Thérèse Charmasson, Recherches sur une Technique Divinatoire: La Géomancie dans l’Occident Médiéval, Geneva: Librairie Droz; Paris: Librairie H. Champion, 1980, 281–282). According to Pietro’s method, a digit between 84 (lowest possible Shield Chart sum) and 128 (highest possible sum) is compared to 96, which is the number resulting from adding up all the points in the sixteen geomantic figures. The chart sum’s proximity to or distance from 96 then indicates how quickly or slowly the outcome will occur. Additionally, the sum of the first twelve figures in the Shield Chart is traditionally used to calculate the Index and Part of Fortune in the astrological House Chart (John Michael Greer, The Art and Practice of Geomancy: Divination, Magic, and Earth Wisdom of the Renaissance, Newburyport: Weiser Books, 2009, 128).

Suggested Citation (Chicago)

Lespar, Y. “Foundations of Nonastrological Geomancy.” Minor Fracture (blog). January 23, 2024. https://minorfracture.blog/2024/01/23/foundations-of-nonastrological-geomancy/

Last Revised: 03-23-2025

Featured image by Peter Hammer on Unsplash

This was the most helpful resource I’ve read for geomancy interpretation techniques. Thank you so much for sharing. It’s very much appreciated. 🖤

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re most welcome. Thank you.

LikeLike

I love the direction this methodology is moving. If I understand the implications correctly, the non-astrological methods you are developing based on an amended Tetractys put much greater emphasis on the four elements within the reading. This is exciting because it allows for greater implications and links and with Empedocles and the Presocratics.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Much appreciated, and thank you for pointing out the pre-Socratic implications. This is certainly a connection that I’m excited to explore.

LikeLike

It’s generous of you to offer these documents to the geomantic community as free downloads! Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re very welcome. I hope they help.

LikeLike

I have enjoyed reading your non astrological geomancy interpretations. I appreciate you sharing this way of casting and reading a chart.

LikeLiked by 1 person